|

| Image source: Jim Hood a.k.a. GearedBull, via Wikimedia Commons |

by Tom Haushalter

As well as it touts its (fiercely protected) natural, mountainous beauty, its cheeses and fall foliage, and its excellent skiing, Vermont nearly belies its own quaint Main Street charm with its independent, self-reliant spirit—hardly more vigorously expressed than in the aftermath of floods and destruction caused by 2010's Tropical Storm Irene.

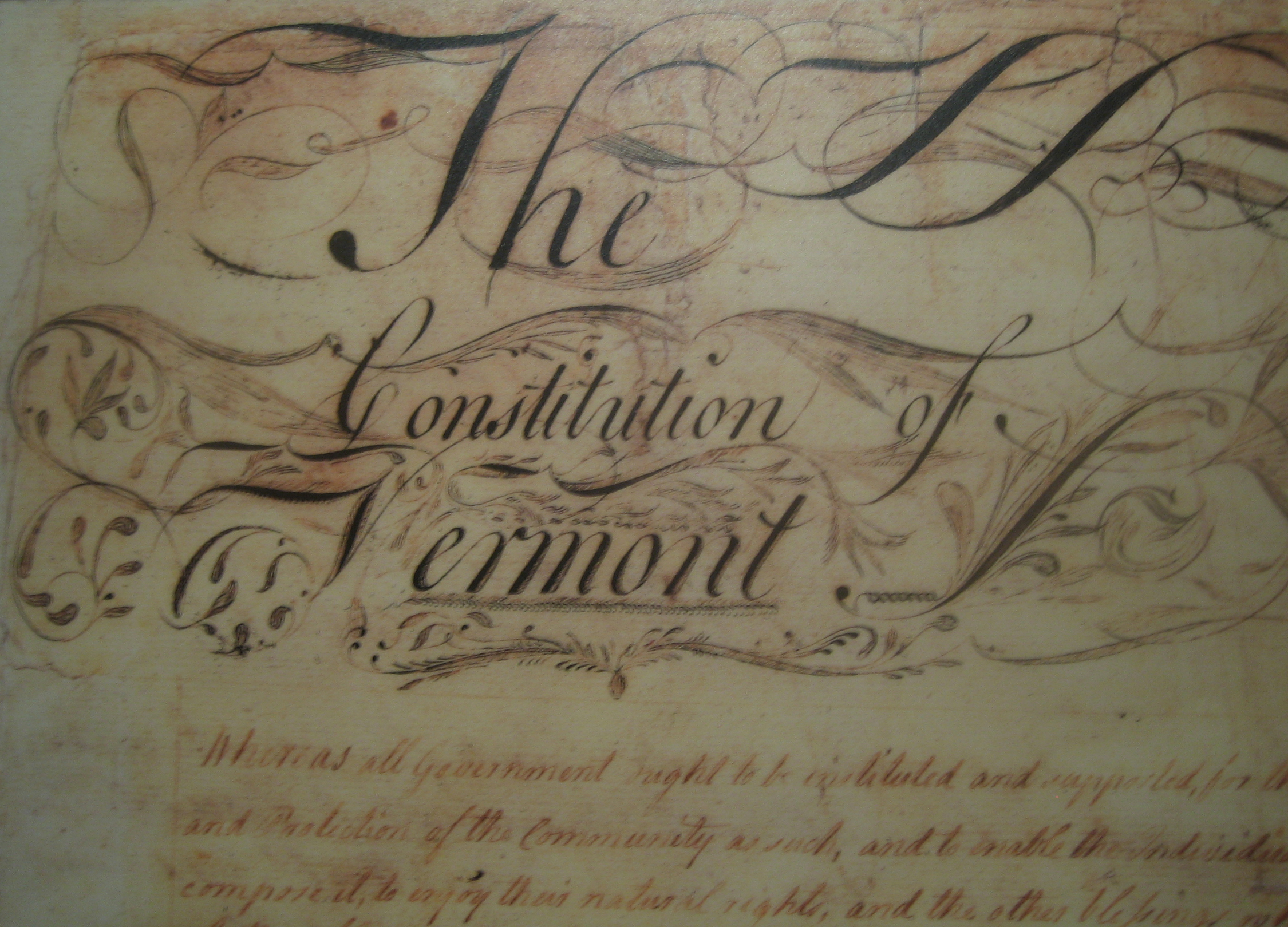

Vermont's individualism runs as deep as January accumulations in the Northeast Kingdom, as tall (in legend) as Ethan Allen, and as far back, let's say, as 1777, when a small congress of men drew up a constitution inside a tavern in the town of Windsor, adopted it, and formed the Republic of Vermont. The republic would last until 1791, when Vermont was admitted as America's 14th state. But among the laws in Vermont's founding document that remained—and the only of its kind in the fledgling agrarian nation—was the abolition of slavery.

In part because Vermont had outlawed slavery, comparatively, so early—shy of a century before America would—it came to be regarded as a bastion of unhampered humanity, a refuge from prejudices institutionalized everywhere else, and a place to be generally left alone if one so pleased.

But a new book just released from the Vermont Historical Society, titled The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810, by University of Vermont professor Harvey Amani Whitfield, shows that even its lone abolitionism wasn't quite as absolute in those early years as anybody would like to believe. The documents that Whitfield uncovers, including bills of sale and court documents, indicate that blacks were still being used as slaves. In an interview with Vermont Today, Whitfield says:

If you were black in Vermont in the 1780s, you could vote, take a white person to court and own property. But at the same time you could be kidnapped or your children held as slaves. Slavery just didn’t end—it was a longer process that took at least 30 years.Whitfield also says that while he doesn't intend the book to amount to a "gotcha" moment in the history of free Vermont, it's no less necessary to make known the state's difficulties in enforcing the law, where in numerous towns discrimination persisted in one form or another. “It doesn’t mean the founders didn’t take an important step,” he said, “but there is a difference between ending slavery and establishing meaningful freedom.”

*

In 1946, an African American named Will Thomas moved his family to Vermont. Fed up with a culture of endless racism, from his birth home in Kansas City to his youth in Chicago, all the way to California, there Thomas and his wife dared to leave the U.S. for Haiti and to live free of racial prejudice. But he decided to give his country one more chance, hoping all the things he'd read about Vermont held true.

Last fall, UPNE member Northeastern University Press brought back into print Will Thomas's phenomenal memoir, The Seeking, originally published in 1953. Thomas' story begins in that present day, with him and his family on the cusp of moving to Vermont. Throughout their doubt-ridden transition and acclimation to country life, Thomas intersperses crucial formative scenes of his youth, assembling an intimate portrait of one man's evolving racial identity in the early 20th century.

Last fall, UPNE member Northeastern University Press brought back into print Will Thomas's phenomenal memoir, The Seeking, originally published in 1953. Thomas' story begins in that present day, with him and his family on the cusp of moving to Vermont. Throughout their doubt-ridden transition and acclimation to country life, Thomas intersperses crucial formative scenes of his youth, assembling an intimate portrait of one man's evolving racial identity in the early 20th century. In the post-war moment that The Seeking is written, before the rise of the civil rights movement, Will Thomas searches for America's redemption—for "meaningful freedom"—in Vermont. His family would be joining about 400 other African Americans who called Vermont home, scarcely one-tenth of one percent of the population then. Would the place make up in welcoming spirit what it lacked in actual diversity?

The townsfolk of Westford, where Thomas settles, aren't outwardly unkind, but they aren't really sure, either, what a young black family is doing there. The local reaction verges on passive aggression, manifested in slow drives past the Thomas' house, staring into their windows. If not racism in the clearest sense, their prejudice, as Thomas perceives it, is couched in questions like, "How come you left sunny California for chilly ole Vermont?"

Gradually, folks do make themselves known and helpful to Thomas and his family, effectively making them part of the community, but the pangs of being outsiders don't subside entirely.

On a walk around local roads one day, noting the disused grist mill and an abandoned farm house "with fallen roof, sagging timbers, paneless windows, its nearby outbuildings having become anonymous piles of rotting wood," Thomas meditates on

how it was—how it really was—in the early days and later; and in this or that desolate spot. I speculated on what grim drama might have been played out there, between long-dead men, white or red, or perchance a vagrant black, such as a slave skulking beneath the Northern star toward Canada, and freedom.In Thomas' experience of Vermont, and in any telling of its past (and present), as is the case anywhere, the picture is far from spotless. And the injustices—often unspeakable and, unlike Thomas', unwritten about—remain inexcusable. But history told well does not ask to be excused. Its purpose is to enlarge our understanding of the "grim drama" in order to better shape the present scene and acts to follow.

Freedom! That was what all men had sought in those harsh yesterdays: white men grimly determined to break their thrall to king and priest ... seeking this great, rich land, and the freedom they so fiercely desired.

But was it not freedom for themselves alone they really sought? Else why had they denied it to the red men from whom they tore the land, and to the African blacks whom later they had kidnapped to be their slaves?

But in Vermont, I reminded myself, men had not been like that then.

Yes, but what of now?

I did not know, not even as weeks became months. I wasn't sure, wasn't at all sure.

In Vermont, Will Thomas seeks a sense of belonging, and comes to find it—perhaps through mutual discomfort and dogged persistence—in the people who learn not only how to "profess racial tolerance [but] to practice such sentiments in day-to-day living."

ALSO OF INTEREST:

Discovering Black Vermont: African American Farmers in Hinesburgh, 1790–1890, by Elise A. Guyette

Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815–1860, by Harvey Amani Whitfield

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.