Season's greetings from UPNE!

It's that wonderful time of year when we must remind ourselves that it is a time for giving. To give is the season's true meaning, we keep hearing.

And no one's denying that. Books, for instance, make excellent gifts to give. To friends and family...and to yourself. We think a book is one of the few things in life that's worth bending the rules of the season in order to get.

So in the conjoined spirit of giving and getting, we're thrilled to offer a 35% discount on the following selection of books published by UPNE and our imprint ForeEdge this year.

To receive the discount, click on the book image or title and use discount code E114EW when placing your order on UPNE.com. The discount will extend through the end of the day, December 31, 2014.

Share this post with friends and family! And happy reading!

A no-holds barred, from-the-trenches account of the campaign to win and protect the freedom to marry in America.

Selected by Slate as a Best Book of 2014, calling it "a timeless story of a fierce and vital fight, fast-paced and marvelously detailed."

Hardcover,

The Court-Martial of Paul Revere: A Son of Liberty and America's Forgotten Military Disaster, by Michael M. Greenburg

Bernard Cornwell calls this book "by far the best account of Revere's life...beautifully written, exhaustively researched, judiciously fair.:

And be sure to brush up on the 7 reasons everyone hated Paul Revere.

Hardcover, $29.95 $19.50

Dog Whistles, Walk-Backs, and Washington Handshakes: Decoding the Jargon, Slang, and Bluster of American Political Speech, by Chuck McCutcheon and David Mark

An entertaining election-year (or any year!) guide to the language of the electeds, spin-meisters, and flacks of American politics.

Paperback,

With ingenuity born of desperation, President Truman overcame the doubters (within his own party), the haters, and the infamously do-nothing Congress to recapture the presidency and, perhaps, save America.

The Wall Street Journal calls White's "a far more compelling account of just how Harry gave 'em hell—the campaign's war cry—than the gauzy version that has hardened into legend."

Hardcover, $29.95 $19.50

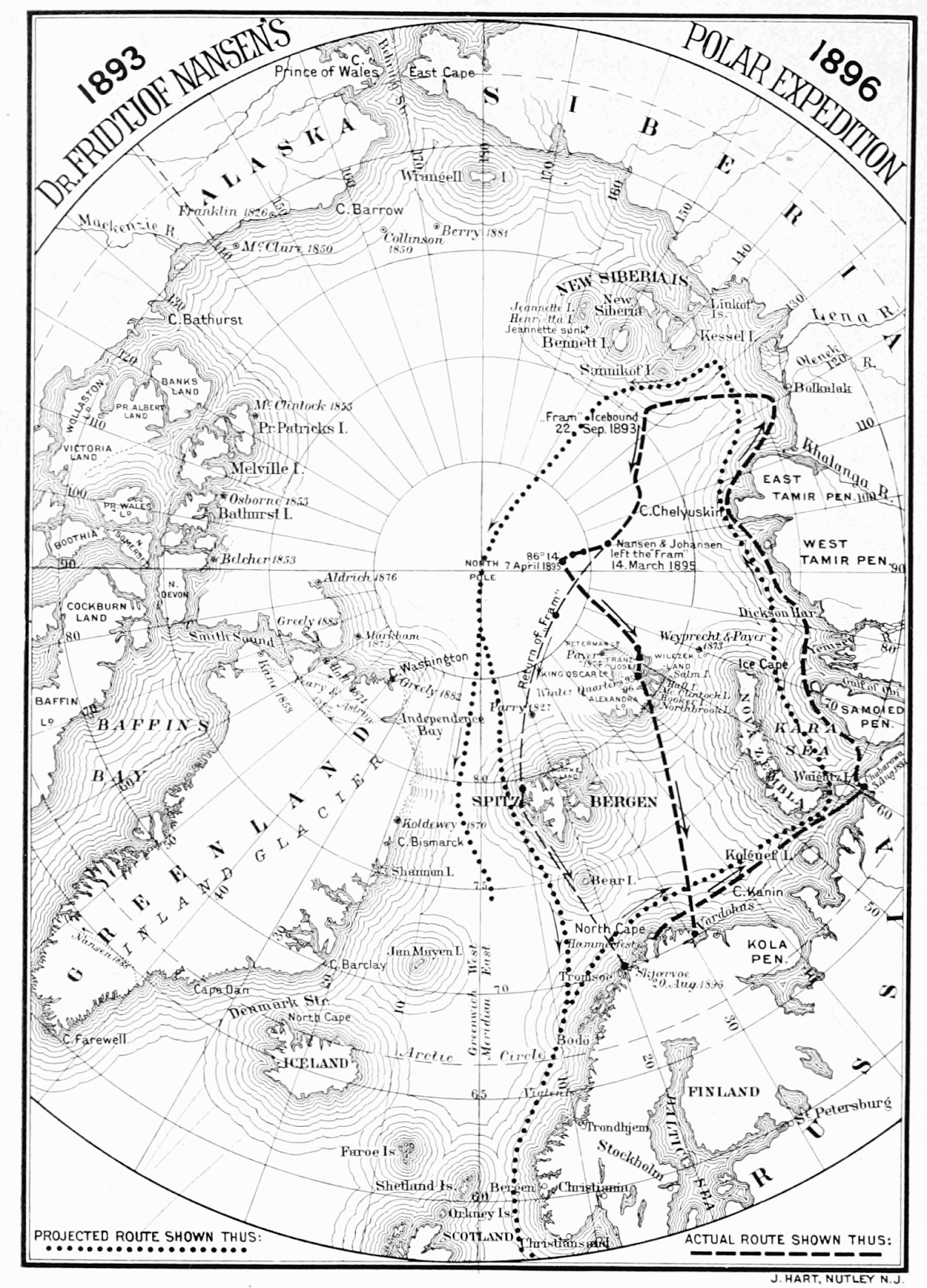

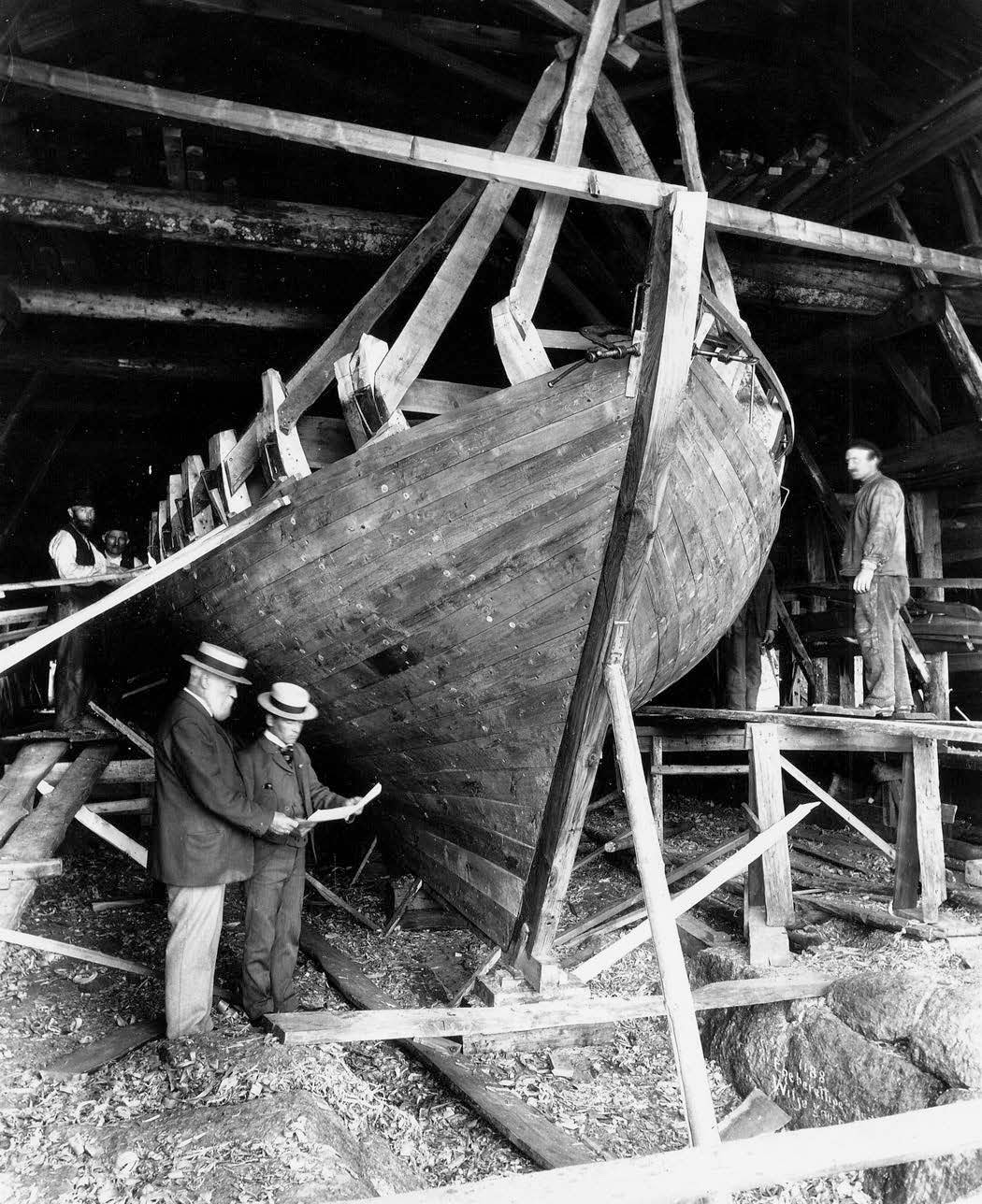

"Ice Ship is as splendidly composed a biography of the magnificent vessel Fram as it is a portrait of the courageous men who sailed her into the daunting Arctic," says bestselling novelist Howard Norman. "Through impeccable research and evocative prose, Charles Johnson brings the last true age of exploration fully alive."

Hardcover,

Dirigible Dreams looks back on a bygone era of when the future of exploration, commercial travel, and warfare largely involved the prospect of wingless flight. Hiam celebrates the legendary figures of this promising technology and revisits many of its triumphs and, of course, its spectacular failures.

Hardcover, $29.95 $19.50

"Victura is more than Graham recounting the sailing experiences of the Kennedys. In this well-researched but warmly written book, Graham sometimes goes several pages describing an election, a Kennedy family intrigue, and then gracefully brings the story back to the sea, showing how, in the best and worst of times, the family pulled together around sailing."—Sailing magazine

Hardcover,

Before today's safety-minded structures of wood and plastic, America's playgrounds were full of tottering seesaws, dizzying merry-go-rounds, and towering slides. Once Upon a Playground is a visual tribute to these iconic structures, celebrating their place in our culture and the collective memories of generations.

Hardcover, $29.95 $19.50

Poor design and wasted funding characterize today's American playgrounds. A range of factors have created uniform and unimaginative play structures, which fail to nurture the development of children or promote playgrounds as an active component in enlivening community space. The Science of Play is a clarion call to use playground design to deepen the American commitment to public space.

Hardcover,